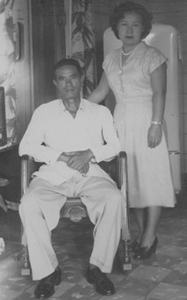

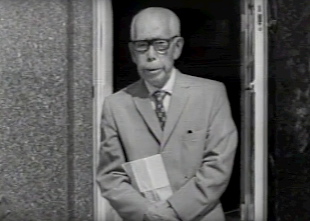

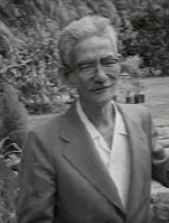

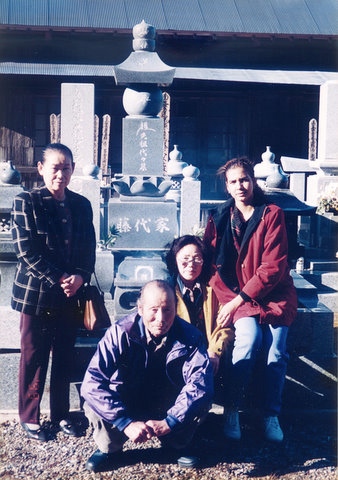

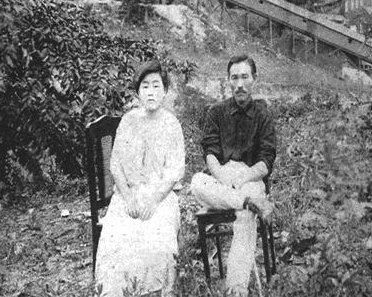

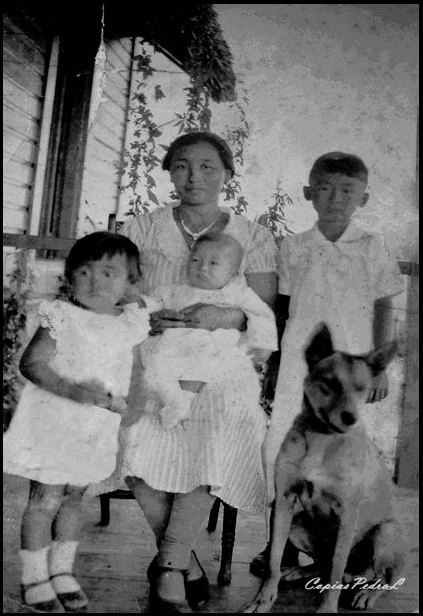

Mosaku Harada fue uno de los inmigrante japoneses más conocidos en Cuba. Fue un agricultor genial y un hombre de gran carisma, quien en alguna ocasión dejó testimonio de su singular y muy exitosa "técnica" agrícola.

—Todas las siembras hablan, yo conozco todo lo que hablan los melones, pepinos, yucas.

—¿Qué le dicen?

—Cada vez que necesita [algo], pidiendo. Cuando necesita agua, pidiendo agua. —¡[Yo] necesita agua! ¡Necesita agua! ¡Mucha sed! —Así dice. Cuando mucho enfermo dice—: ¡Oígame, dolor de pierna, que [yo] necesita medicina! —Cada vez que ellos necesitan, hablando, mata de naranja y mata de mango, todo todo todo hablando. Si no se oye [lo que dicen], no puede cosechar bien. Yo oigo, hay que oír voz de planta, melón pide [lo] suyo, toronja pide [lo] suyo, cada siembra quiere algo distinto. . . .

—Usted tenía una técnica.

—Técnicamente nada, mucha paciencia para trabajar día y noche arriba [de la siembra]. Hay que oír de la mata. —¡Oígame, dueño, necesito agua! —Y hay que dar agua. —¡Oye, ya bastante agua, no más! —Entonces hay que parar el agua. Después abono que pide, hay que darle. Día y noche oyendo . . . la voz [de] la planta, no solo melón, de todo; pidiendo agua, pidiendo seco, y pidiendo abono. Eso es plantación, gente cree que [siembra] no hablando nada, pero sí hablando.

Así era que el famoso agricultor japonés explicaba su éxito agrícola, gracias al cual producía, entre otras cosas, unas sandías gigantes, en su cooperativa de la Isla de la Juventud, Cuba. Esta transcripción combina los testimonios de Mosaku Harada que aparecen en dos documentales cubanos: Japoneses (Idelfonso Ramos, 1981), y Un eterno sembrador (Octavio Cortázar, 1988). Pero la escritura no le hace justicia a su gran carisma y a su modo de hablar tan cubano y, al mismo tiempo, tan japonés, algo que la cámara capta bien.

___________________ENGLISH___________________

Mosaku Harada was one of the most famous Japanese immigrants that lived in Cuba. He was an excellent farmer and a very charismatic man, who, in some occasions spoke about his peculiar and very successful agricultural “technique.”

"All crops talk; I know all that watermelon, cucumber, yuca [cassava] say."

"What do they tell you?"

"Whenever they need [something], asking. When they need water, asking water." "[Me] need water! Need water! Very thirsty!" "So it says. When very sick, it says: "Hey, leg pain, need medicine!" "Every time they need something, [they] talking, orange tree and mango tree, all all all talking. If you don’t listen [to what they are saying], you can’t harvest well. I listen, you need to listen to the voice of the plant, watermelon asks for its share, grapefruit asks for its share, each crop wants a different thing." . . .

"You had a technique."

"Technically nothing, lots of patience and to work day and night to stay on top of things. You have to listen to the plant." "Hey, owner, I need water!" "And then you have to give water." "Hey, enough water, no more!" "Then you stop water. Later comes the call for fertilizer, you have to give them [fertilizer]. Day and night listening . . . to the voice [of] the plant, not only watermelon, every crop; asking for water, asking for dry, asking for fertilizer. That is harvest; people think that [crops] not talking anything, but they really talking."

That is how the famous Japanese farmer used to explain his agricultural success, which allowed him to produce, among other things, huge watermelons, in his co-op in the Island of Youth, Cuba. The above quote is a transcription (translated from Spanish) of Mosaku Harada’s commentaries as recorded in two Cuban documentaries: Japanese People (Japoneses, Idelfonso Ramos, 1981), and Forever a Farmer (Un eterno sembrador, Octavio Cortázar, 1988). But writing doesn’t do any justice to his great charisma and to his way of sounding so Cuban and, at the same time, so Japanese, which the camera captures well.