Si agrupamos muchas de las anécdotas que actualmente existen guardadas en libros, documentales, y en la memoria de muchos nikkeis, podemos crear una historia muuuuuuy larga, que, como un "running-story", funcione como una historia que se publica en varios artículos.

En cada edición de esta historia-que-sigue se narrará un nuevo episodio de la vida de la comunidad cubano-japonesa, con algunas anécdotas muy conmovedores, otras de mejor humor.

Y entonces, para echar a "correr" esta narración de una vez, comencemos con una de risa.

En cierta ocasión, mientras compartía con un grupo de sus compañeros de aventura unas cervezas y un poco de atún, [Ueno] se dirigió al joven que atendía el establecimiento para solicitar unos "paríos"; petición a la cual respondió el dependiente de forma negativa mientras se encogía de hombros. Entonces el japonés insistió nuevamente: - ¡Paríos, Paríos!... pero una vez más el criollo, sorprendido por aquel sustantivo desconocido, volvió a patentar su ignorancia al respecto. El resto de los japoneses miraban con simpatía aquella situación, en la que uno y otro se esforzaba por lograr un entendimiento respecto a los famosos paríos; hasta que no pudiendo lograr comunicación verbal con el joven dependiente; consciente del aprieto por el que atravesaba este, [Ueno] salió al patio y regresó con un fino espantillo [espartillo] de hierba, se rozó los dientes en presencia del empleado y continuó diciendo: -Esto ser paríos... Una sonrisa de satisfacción llegó a ambos, entonces el que yacía tras el mostrador, haciendo un gesto afirmativo, se dirigió al entrepaño más cercano, agarró una cajetilla de palillos de dientes y la puso en la mano diestra del forastero, que de inmediato retribuyó el gesto con una monedita de cinco centavos.

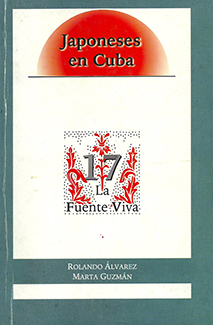

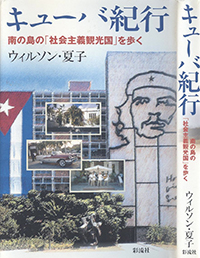

El historiador cubano Rolando González Cabrera narra esta anécdota en su libro La saga japonesa en el occidente cubano (Pinar del Río: Ediciones Loynaz, 2009, p.61-62). Su investigación se centra en los inmigrantes japoneses y descendientes de la región de Pinar del Río. Su libro aborda mucho aspectos históricos relacionados con esta migración; pero uno de los elementos más interesantes de este trabajo es que conecta esta visión histórica general con los testimonios de niseis, así como de cubanos que estuvieron en contacto con esta migración.

___________________ENGLISH___________________

By putting together many of the anecdotes that nowadays “live” in books, documentaries, and in the memory of many nikkeis, it is possible to create a very long story. It would be like a “running-story” that is published in various articles, in which each edition narrates a new (moving or humorous) episode in the life of the Cuban-Japanese community.

But let’s “run” this story once and for all, and do it with some laughter.

In one occasion, [Ueno] was sharing some beers and tuna with a group of friends, when he suddenly walked towards the young man who was serving at the establishment, and asked for “paríos”. The server shrugged his shoulders and answered in a negative way to the request. The Japanese man insisted: - Paríos! Paríos!... but the Cuban server replied in the same way, not being able to understand the meaning of the unknown word. The Japanese friends [of Ueno] were the sympathetic spectators of this situation in which both men were trying to reach an understanding about the famous paríos. Aware of the difficult position the server was going through, [Ueno] went outside and came back with a strand of grass, rubbed it against his teeth in front of the man and said: -This be paríos… They both smiled satisfied. The server nodded affirmatively, went over the closest shelf, grabbed a pack of toothpicks and put it in the foreigner’s right hand [in Spanish toothpicks are called “palillos”, leading to a confusion when Ueno pronounced it with “r” instead of “l” sound, pa

Cuban historian Rolando González Cabrera narrates this story in his book Japanese Saga in Cuba’s Western Region, p.61-62 (Pinar del Río: Ediciones Loynaz, 2009). His investigation focuses on the Japanese immigration in Pinar del Río province, for which he touches on national and international historical aspects. But one of the most interesting aspects of his book is the combination of this general historical vision with many testimonies of various nisei, and Cubans that had contact with this immigration in the western region.