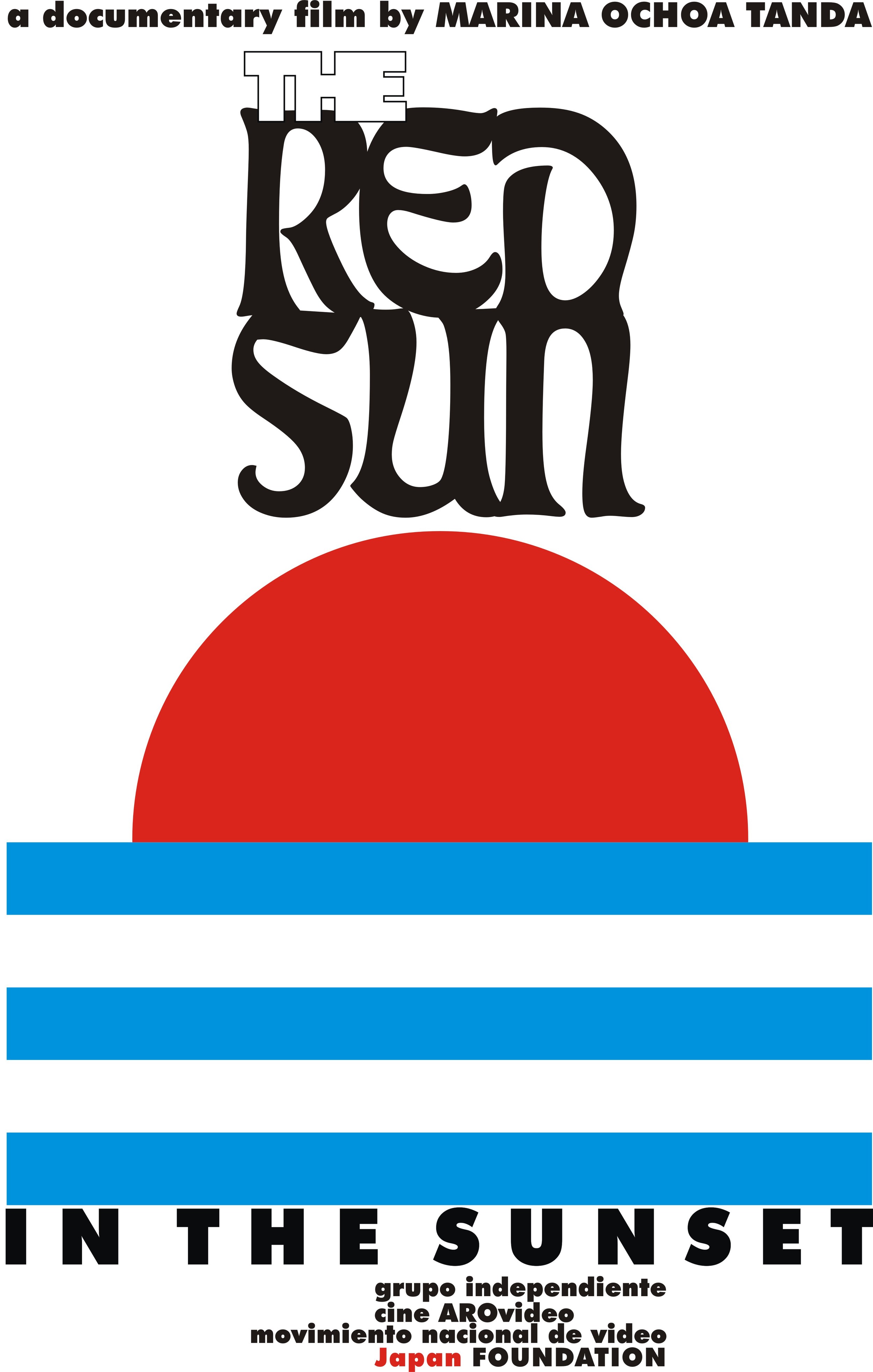

En anteriores “Running-stories” e historias sobre “Sitios” escribí sobre el aporte de los inmigrantes japoneses al panorama cultural cubano. En esas ocasiones recordé los métodos agrícolas de Mosaku Harada en la Isla de la Juventud, la labor de Kanji Miyasaka como intérprete en el Instituto Cubano de Deportes, Educación Física y Recreación (INDER), y el hecho de que los inmigrantes japoneses introdujeron una técnica de pescar bonito que todavía se practica en Cuba. A mi lista le queda mucho espacio en el que incluir otros nombres e historias. Por ejemplo, Kenji Takeuchi fue el fundador técnico del Orquideario de Soroa, Zenshun Ishikawa y Goro Naito trabajaron como intérpretes en la Flota Cubana de la Pesca, y Goro Enomoto desarrolló su vida profesional en el Instituto Cubano del Arte e Industria Cinematográficos (ICAIC). Aún así, estas siguen siendo listas increíblemente incompletas, una buena razón para seguir indagando en la vida cubana de los inmigrantes japoneses, y en las vidas de sus hijos e hijas, puesto que considero que la generación nisei todavía es un terreno en el que queda mucho por explorar. Por ahora, saltémonos tres generaciones para conocer a la cantante cubana Hakely Nakao, mi interés por su historia se debe a que hasta donde conozco no hubo músicos profesionales entre los issei.

Aunque sé que muchos inmigrantes japoneses hacían gala de sus dotes musicales en reuniones familiares y eventos de la comunidad, en los que cantaban, bailaban y tocaban el shamisén, entre otros instrumentos.

La siguiente entrevista con Hakely es la primera en una historia más larga por la que "correrán" otras conversaciones con jóvenes músicos cubano-japoneses.

La música y los/las nikkeis: La cantante Hakely Nakao

La música y yo

A los siete años, mientras cursaba el Segundo Grado de la enseñanza primaria, fui seleccionada para integrar un círculo de interés de música, junto a unos veinte niños de la misma edad. En ese momento vivía en Nueva Gerona, la capital de la Isla de la Juventud. Allí existió una gran maestra, instructora, promotora cultural, pedagoga, pianista y acordeonista, quien dirigía las clases de los sábados en la sede de la Escuela Vocacional de Arte Leonardo Luberta Noy. Durante más de 6 meses como parte de ese proyecto, entre canciones, poesías y clases de introducción a la teoría de la música, se fue develando mi pasión por la expresión musical. También mi tío materno, aficionado de la música y amante por excelencia de los instrumentos de percusión, había descubierto que desde muy pequeña le seguía rítmicamente y era muy creativa para desarrollar motivos polirrítmicos mientras él tocaba, sin que yo perdiera el pulso y la métrica correspondientes.

Hakely Nakao

Ambos eventos influyeron en que en septiembre de 1990 ingresara a la escuela antes mencionada. No tenía ninguna pretensión de que fuera mi futuro, aunque sí tuve la oportunidad de tener una familia que me apoyó e impulsó a desarrollar un talento que solo la maestra Olga (no recuerdo su apellido) había descubierto seriamente. Así comencé mis estudios de Piano, que concluyeron en 1997. Posteriormente decidí estudiar la especialidad de Dirección Coral en la Escuela Nacional de Arte (ENA), con la Maestra María Felicia Pérez, quien es la directora del coro Exaudi. Mi estudios de música concluyeron en el año 2006 cuando me gradúe del Instituto Superior de Arte (ISA). Por más de once años he estado cautivada por el mundo de la música vocal, una pasión que le agradezco a mi maestra.

¿Tradición musical en mi familia?

Si por tradición musical te refieres a tener a algún músico profesional activo o inactivo en mi familia, o un ambiente de descargas musicales hogareñas que propiciara mi inclinación por ese arte, mi respuesta es: no. Provengo de una familia en la que la música era un mero entretenimiento cotidiano que brindaba compañía mientras se limpiaba, se cosía, y durante las fiestas. Crecí escuchando al mencionado tío y los (algunas veces descontrolados) timbalazos que le propinaba a los tambores que él mismo preparaba o reparaba en aras de desarrollar su hobby musical. Escuchaba lo que ponían en la radio, a mi abuela materna cantando a Sindo Garay y recitando a José Martí, y a mi mamá, cada noche intentando acercarse a la entonación correcta de la tradicional nana Señora Santana (lo cual todavía no ha logrado). También, mi papá era un bailador muy cotizado en su pueblo natal.

La tradición musical la comencé yo, y la ha continuado mi hermana pequeña, al escoger también la música como profesión, (me imagino que) inspirada en mis largas horas de estudio frente al piano.

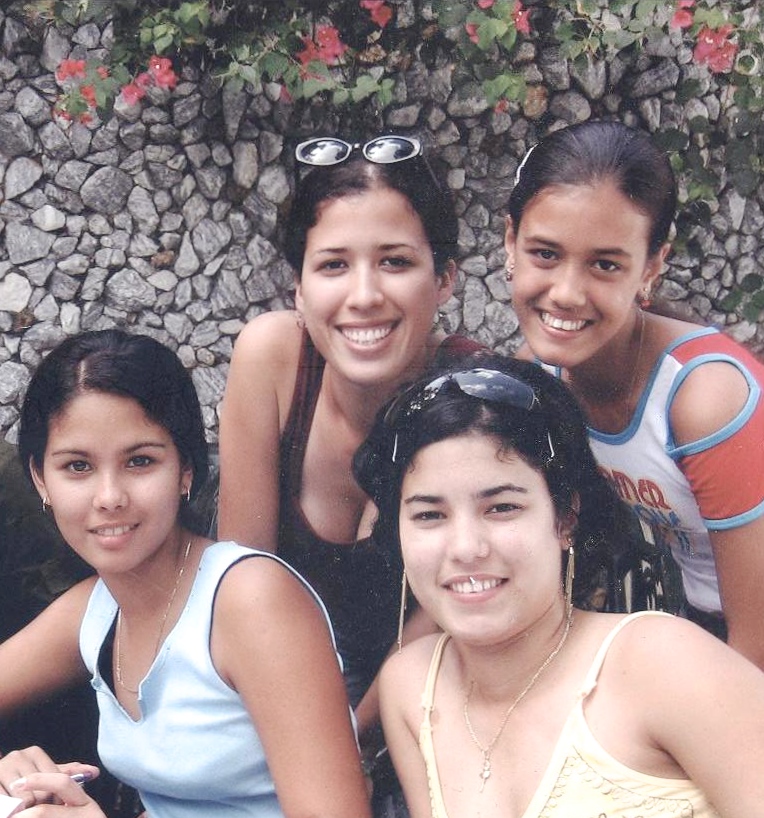

Hakely Nakao (second from right), singer and founder of the vocal group Zambá.

Ser estudiante

La Universidad de las Artes o Instituto Superior de Arte (ISA) en La Habana fue la institución en la que cursé mi carrera de Dirección Coral a nivel superior o graduado, de la mano de María Felicia Pérez. Si solamente escogiera una experiencia como lo que más me gustó, sería muy ingrata con los grandes momentos que pasé. Disfruté mucho mi vida de estudiante, mucho más la que viví en la ENA (Escuela Nacional de Arte) que la del ISA. Fueron años que compartí con músicos excelentes, amigos entrañables que hoy son importantes exponentes de la nueva generación de músicos en Cuba, con quienes compartí los mismos sueños y ganas de hacer.

Mi familia y lo japonés

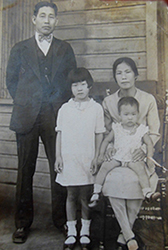

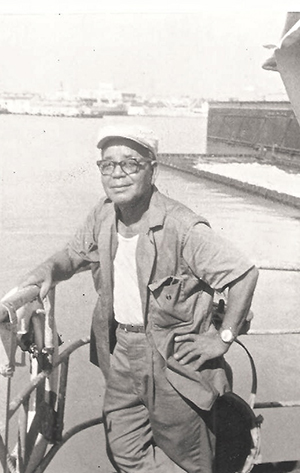

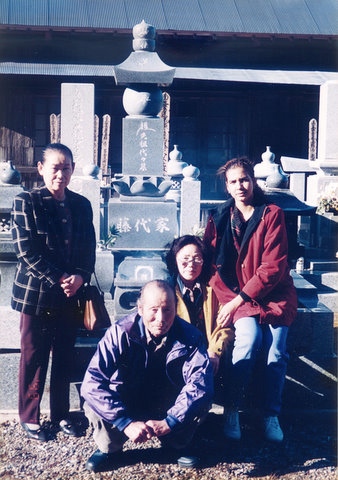

Si recuerdo correctamente, mi abuelo paterno emigró hacia Cuba desde Yokohama en 1944. No lo conocí, mi papá me cuenta que era un hombre de muy pocas palabras, siempre pensativo y pausado. Salió de Japón huyendo de la guerra, y al llegar a Cuba se instaló en la zona norte de la provincia de Holguín. Allí comenzó su vida como ciudadano cubano y organizó una familia con mi abuela, quien era una cubana mestiza. Tuvieron siete hijos, dos mujeres y cinco hombres; ellos nunca lograron entender el idioma japonés y el acento raro con el que su papá les hablaba en español, aunque esto no impidió que le tuvieran un respeto paralizante que ha llegado hasta mi generación. Mi abuelo nunca regresó a Japón; pero mantuvo correspondencia con su familia japonesa hasta su muerte a principios de la década de 1970, a partir de esa fecha el vínculo se detuvo.

Así, la conexión entre lo japonés y yo ha sido solo una pasión que mi papá y sus hermanos me inculcaron, ellos repetían lo poco que recordaban de lo que les había enseñado su papá. Crecí sabiendo que eso era lo que diferenciaba a mi familia de otras familias cubanas, una peculiaridad japonesa que se hacía más evidente debido a la presencia de una fuerte comunidad japonesa en la Isla de la Juventud. A través de esta comunidad conocí el idioma y las tradiciones. Gracias a las constantes reuniones entre familias de descendientes que activamente trabajaban en esa región del país, se ha podido mantener viva la expresión de una cultura japonesa, ya aplatanada en Cuba.

"China"

En Cuba siempre fui la hija del chino (como las personas se referían a mi papá), me llamaban chinita. Según mi mamá, de pequeña solía hacer la aclaración: chinita no, japonesa.

Cuando crecí ya no me tomé más el trabajo de hacer aclaraciones, ante la costumbre tan popular entre los cubanos de asumir que ciertas facciones (ojos rasgados, pelo negro lacio) significan ser chino, sin diferencias entre asiáticos.

Descendencia japonesa y profesión musical

En el año 2003, los miembros del Comité Gestor de la Sociedad Cubano Japonesa tuvieron la idea de crear vínculos que unificaran a las familias de descendientes en la ciudad de La Habana, como resultado de esto mi hermana y yo creamos un coro que Francisco Miyasaka nombró Coro Fuji. El proyecto no tenía muchas pretensiones musicales, pero las reuniones con los descendientes que aceptaron formar parte de este grupo se convirtieron en un buen pretexto para acercarme a la música tradicional japonesa, a las canciones infantiles y populares de Japón, al mismo tiempo que aprendí sobre estilos e instrumentos tradicionales.

Cada sábado nos reuníamos a las tres de la tarde en la casa de un descendiente, en el barrio del Vedado, las prácticas duraban dos horas entre canciones y risas, tiempo en el que tuve la oportunidad de acercarme como nunca antes al mundo japonés. De la mano y guía del Sr. Miyasaka y con el asesoramiento incansable de la Sra. Naka (Kazuyo Nakagawa) logramos crear una gran familia. Unos se divertían cantando las canciones que solían entonar sus padres o abuelos; otros, como yo, descubrían por primera vez unas melodías que pronto serían parte de nuestra cotidianidad. El Coro Fuji estaba integrado por veinticinco descendientes de segunda, tercera, cuarta y quinta generación, de todas las edades y residentes en La Habana; fue una de las experiencias que más ha aportado, simultáneamente, a mi vida profesional y personal.

Fue necesario crear métodos nemotécnicos para enseñar las melodías y las letras de las canciones, por ejemplo, para desarrollar la correcta pronunciación de las palabras aunque ninguno de nosotros tuviera la menor idea del significado de lo que estaba cantando. Por supuesto, siempre contamos con las traducciones personales que el Sr. Miyasaka y la Sra. Naka preparaban previo al montaje de las canciones. Nuestro repertorio sobrepasó una decena de canciones, entre ellas: Akatombo, Sakura, Konnichiwa Akachan, Furusato, el Himno Nacional de Japón y cantos de celebraciones tradicionales como el Obón.

Japón, familiares y colegas de profesión

Ir a Japón es una meta por cumplir. Poder contactar con mi familia japonesa sería un sueño realizado y un deseo cumplido para mi papá y mi familia en general.

He tenido la dicha de compartir en escenarios cubanos con importantes músicos japoneses que han fusionado elementos melódicos y rítmicos cubanos y japoneses a partir de nuestra música clásica y popular. Ellos han dejado interesantes huellas en grabaciones discográficas, o en momentos imborrables que solo se aprecian en actuaciones en vivo. Algunos ejemplos son: Antonio Koga, Ai Kanzaki, Yokosawa Hiroaki, Tamaki Hagihara y Yasuji Ohagi, entre otros.

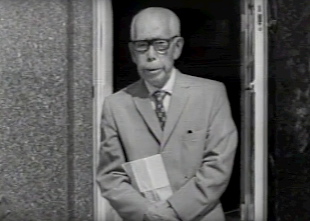

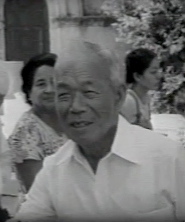

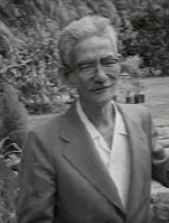

(Fotos cortesía de Hakely Nakao y Kenji Iwasaki).

Entrevista a Hakely Nakao, por Miharu Miyasaka. Enero 2014.

___________________ENGLISH___________________

In previous “Running-stories” and stories of “Sites” I wrote about Japanese immigrants' contribution to Cuban culturescape. I remembered Mosaku Harada's agricultural methods in the Island of Youth, Kanji Miyasaka's work as an interpreter for the Cuban Institute of Sports, Physical Education and Recreation (INDER), and how Japanese immigrants introduced a bonito fishing technique that it's still being practiced in Cuba. My list has plenty of room for more names and stories. For instance, Kenji Takeuchi was the technical founder of Soroa's Orchid Garden, Zenshun Ishikawa and Goro Naito worked as interpreters in the Cuban Fishing Fleet, and Goro Enomoto spent his professional life at the Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry (ICAIC). Still, these are greatly incomplete lists, for which I intend to keep looking into the Cuban life of Japanese immigrants, even further, into their sons and daughters’ lives, since I believe there's plenty to discover about the Nisei generation. For now, lets jump ahead three generations to meet Cuban Sansei Hakely Nakao. My interest in her story stems from the fact that to my knowledge there weren’t professional musicians among the Issei. Although I’ve heard and read stories about Japanese immigrants’ musical prowess at family gatherings and community events, in which they used to sing, dance and played the shamisen, among other instruments.

The following interview with Hakely is the front-runner of a longer story that will include other conversations with young Cuban Japanese musicians.

Music and Nikkei: Singer Hakely Nakao.

Music and I

When I was seven years old, attending Grade 2, I was selected to be part of a music interest group of twenty children of the same age. At that time I was living in New Gerona, the capital of the Island of Youth. There lived a great professor, cultural promoter, educator, piano and accordion player, who taught those Saturday classes at the Vocational Art School Leonardo Luberta Noy. My passion for music started to grow during that six month project, immersed in songs, poetry and introductory lessons on musical theory. Also, my maternal uncle is a music aficionado and a big fan of percussion instruments. Since I was little he noticed that I was good at following his rhythm, and very creative at producing polyrhythmic passages without ever loosing the corresponding pulse and metric.

Both events were influential in my enrollment at the aforementioned school. I didn’t expect music to be my future although I did have a family that supported and encouraged me to develop a musical talent that only professor Olga (I don’t remember her last name) was able to take into serious consideration. Then I started Piano studies, until 1997. Later on I specialized in Choral Conducting at the National Art School (ENA), under the guidance of professor María Felicia Pérez, who is the director of the Exaudi Choir. I finished my music studies in 2006 when I graduated from the Higher Institute for the Arts (ISA). For more than eleven years I’ve been captivated by the world of choral music, for which I’m grateful to my professor.

On being a student

I pursued a graduate degree in Choral Conducting at the Arts University or Higher Institute for the Arts (ISA) in Havana, under the guidance of María Felicia Pérez. It would be unfair to only choose one favorite experience, since I enjoyed very much my student life, perhaps more at the National Art School (ENA) than at ISA. I spent those years with excellent musicians and dear friends, who nowadays represent a new generation of Cuban musicians, with whom I shared dreams and motivations.

Music tradition in my family?

If by music tradition you are referring to a family member that is a professional musician, whether active or not, or to a childhood in which musical themes were performed at home hence influencing my musical interest, then I would answer: no. For my family, music was a daily entertainment that would bring company to the acts of cleaning, sowing, or to parties. I grew up listening to the aforementioned uncle and his (sometimes out of controlled) pounding on self-made or self-repaired drums with which he pleased his musical hobby. I used to listen to the radio, to my maternal grandmother singing Sindo Garay’s tunes and reciting José Martí’s poems, and to my mother, who every night tried to reach the right intonation when singing the traditional lullaby Mrs. Santana (something not accomplished by her yet). Also, my father’s dancing skills were well known in his hometown.

I started a music tradition in my family. My younger sister has carried it further by also choosing music as her profession, (I imagine) inspired by my long hours studying piano.

My family and lo japonés

If I remember correctly, my paternal grandfather came to Cuba from Yokohama in 1944. I didn’t know him; my father tells me that he was a man of few words, always pensive and calm. He left Japan fleeing the war. Once in Cuba he settled down in the northern area of Holguín province, where he started his life as a Cuban citizen as well as a family with my grandmother, a Cuban of mixed race (or mestiza). They had seven children, two women and five men, who never quite understood their father’s Japanese language and peculiar accent when speaking Spanish. However, this didn’t stop their father from inspiring outmost respect, even to my generation. My grandfather never went back to Japan; but he kept in contact with his Japanese relatives until his death in the 1970s, from then on the contact stopped.

Therefore, my Japanese connection is a passion that stems from my father and his siblings’ influence; they tried to keep alive whatever little they remembered having learned from their father. I grew up acknowledging that difference between my family and other Cuban families, a Japanese peculiarity that was more evident given the presence of a strong Japanese community in the Island of Youth, through which I learned about Japanese language and traditions. Thanks to the frequent meetings of families of descendants actively working in that region, expressions of Japanese culture were kept alive, although now rooted in Cuba.

"Chinese"

In Cuba, I was always the daughter of the Chinese (how people referred to my father), I was the little chinese (or chinita). According to my mother, when I was little I used to tell people that I was not Chinese, but Japanese.

When I grew up I didn't bother anymore with these clarifications, it is very popular in Cuba to think of a person with certain features (slanted eyes, black straight hair) as Chinese, not differentiating between Asians.

Japanese descent and music profession

In 2003, members of the Cuban Japanese Society Organizing Committee had the idea of creating links that would bring families of descendants living in Havana City closer to each other. As a result, my sister and I started a choir that Francisco Miyasaka named Fuji Choir. The project didn’t have many musical expectations, although those meetings with the descendants who accepted to be part of the group became a pretext for me to come closer to Japanese traditional music, children and popular songs, at the same time I learned about styles and traditional instruments.

We would meet every Saturday at three in the afternoon, in the house of a descendant that lived in Vedado neighborhood, and practices would last two hours among songs and laughs. During that period of time my connection to a Japanese world was closer than ever before. Under the guidance of Mr. Miyasaka and the determined advice of Mrs. Naka (Kazuyo Nakagawa) our group became a great family. Some would enjoy singing tunes previously sung by their parents or grandparents, others, like myself, were discovering for the first time melodies that soon would become familiar. Twenty-five descendants of different ages integrated the Fuji Choir, ranging from second, third, fourth and fifth generations, all residents of Havana City. It was one of the most rewarding experiences in terms of simultaneous professional and personal contributions.

It was necessary to develop mnemonic methods in order to teach melodies and lyrics of songs, for example, to have the correct pronunciation, even when we didn’t have a clue about the meaning of the words we were singing. Of course, Mr. Miyasaka and Mrs. Naka always prepared personal translations of the lyrics before we began working on the piece. Our repertoire included over a dozen songs, among them: Akatombo, Sakura, Konnichiwa Akachan, Furusato, Japan National Anthem and songs from traditional festivities such as Obon.

Japan, relatives and fellow musicians

Going to Japan is something that I still ought to do. Being able to get in touch with my Japanese relatives would mean fulfilling a dream of my father and my family in general.

I’ve had the good fortune of sharing Cuban stages with important Japanese musicians whose works have fused Cuban and Japanese melodic and rhythmic elements based on our classical and popular music. They have left traces of these works in recordings, or in unforgettable moments that could only be appreciated in live performances. Some of these musicians are: Antonio Koga, Ai Kanzaki, Yokosawa Hiroaki, Tamaki Hagihara y Yasuji Ohagi, among others.

(Photos courtesy of Hakely Nakao and Kenji Iwasaki).

Interview with Hakely Nakao, by Miharu Miyasaka. January 2014.