Los jardines de Cuba: jardineros japoneses

Al llegar a Cuba las aspiraciones económicas de muchos inmigrantes japoneses se transformaron en diferentes proyectos ocupacionales. Para muchos, la travesía cubana comenzó en el duro paisaje de los campos de caña; pero la mayoría no pudo aguantar la difícil vida del cañero de temporada que debe trabajar bajo un inclemente clima tropical, al cual los japoneses no estaban acostumbrados, y no tardaron en irse en busca de mejores trabajos en pueblos y ciudades.

Así, siguiendo disímiles rutas profesionales llegaron a convertirse en jardineros, tenderos, barberos, agricultores, mineros, trabajadores ferroviarios, pescadores, e incluso heladeros, entre otras actividades. En general los inmigrantes japoneses constituyeron un grupo pequeño y geográficamente disperso que no causó mucha tensión entre los cubanos. A esto hay que agregar que se mantuvieron lejos de estratos sociales y profesionales altos; todos pertenecían a la clase obrera baja. Aunque la nisei cubana Benita Eiko Iha Sashidacuenta una historia muy curiosa en su libro Shamisén, sobre cómo su madre solía trabajar con su esposo (el padre de Benita), quien era barbero; pero un día dejó de hacerlo al darse cuenta de que los cubanos no veían con buenos que una mujer trabajara fuera de su casa.

Los japoneses resultaron muy apreciados, e incluso particularmente solicitados, para trabajar en jardines. Gracias a esta afición de algunos cubanos por su sensibilidad y su arte para el cultivo de flores, la jardinería y el paisajismo, muchos inmigrantes japoneses fueron contratados para embellecer algunas residencias en ciudades y en centrales azucareros. Fue una profesión circunstancial, casi improvisada, puesto que la desarrollaron en respuesta a las condiciones laborales que encontraron en Cuba.

KANJI AND KESANO MIYASAKA

Así fue en el caso de mi abuelo, Kanji Miyasaka, quien, no obstante, llegó a convertirse en el jefe de los jardineros de la mansión del administrador del Central Stewart (hoy Venezuela), en una parte de la provincia de Ciego de Ávila que antes pertenecía a Camagüey. Él dejó la jardinería en la década de 1960, cuando comenzó a trabajar de intérprete en el Instituto Nacional de Deportes, Educación Física y Recreación (INDER); pero aún recuerdo la cantidad de tiempo y atención que le dedicaba a sus flores y plantas, las cuales llenaban la terraza y el patio de su casa. Su flor favorita era la violeta africana, y también le gustaban mucho las hortensias, orquídeas y calancoes.

Uno de los ejemplos más interesantes de la floricultura y el paisajismo de influencia japonesa es la Hacienda Cortina (ahora llamada Parque Nacional La Güira ) en la provincia de Pinar del Río. Rolando González Cabrera explica en su libro La saga japonesa en el occidente cubano que el Senador José M. Cortina contrató a un grupo de inmigrantes japoneses, entre ellos Yuzo Okamoto y Takato Yoshida, para recrear un “universo oriental” en su vasta hacienda. Ellos lograron injertar exitosamente un hermoso jardín “oriental”, con un torii, un estanque, linternas y una “Casa Japonesa”, entre otros elementos, en el impresionante paisaje pinareño.

Así, los jardines privados, sobre todo antes de 1959, se convirtieron sitios importantes para trazar una de las rutas de la presencia de los japoneses en Cuba.

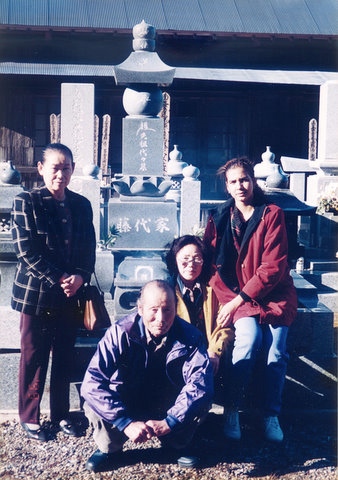

GOHEI ARAKAWA

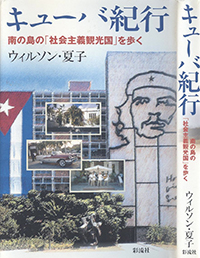

En la foto tomada entre 1948-1952, Gohei Arakawa trabaja como jardinero en el Central Baraguá (ahora Ecuador), en una parte de la provincia de Ciego de Ávila que antes pertenecía a Camagüey. Arakawa fue el Presidente de la Colonia Japonesa en el central. Su nieta, Francys Arakawa, recuerda que su "abuelo era jardinero de las casas de los americanos que trabajaban en el central Baraguá", y que después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial los japoneses en Cuba "no podían trabajar en dependencias de ciudadanos americanos, . . . [pero] en 1948 esto cambió y es en esa etapa que vuelve a trabajos de jardinería".

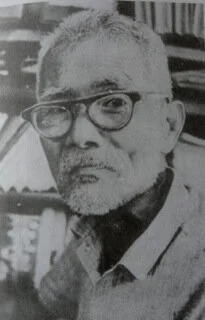

KENJI TAKEUCHI

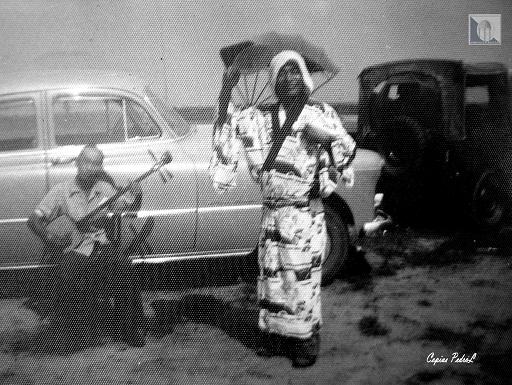

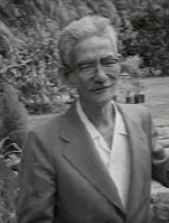

En la foto de 1971, Kenji Takeuchi. Él llegó a ser un reconocido floricultor que contribuyó al estudio de las flores, y a la creación del famoso Orquideario de Soroa. Francisco Miyasaka recuerda que él “trabajó como jardinero y cosas dedicadas a las flores en la casa de Miguel Ángel Quevedo, que fue director de Bohemia muchos años, quien tenía una finca en El Chico. Aparte de eso, Takeuchi tenía . . . con otro socio . . . una florería cerca de 12 y 23 [por el Cementerio de Colón] . . . que se llamaba La Dalia. Ellos allí vendían flores para la gente que iba al cementerio, y las producían por el Wajay”, en una tierrita que Takeuchi había comprado.

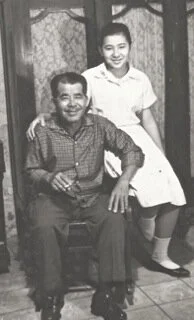

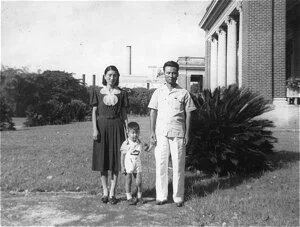

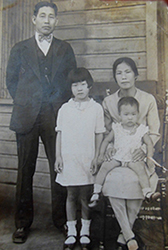

KANJI MIYASAKA Y FAMILIA

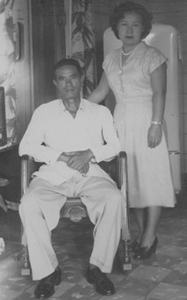

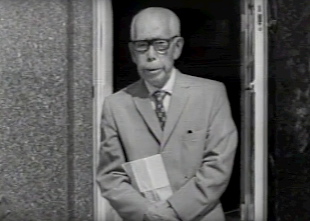

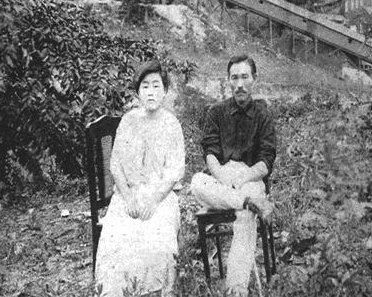

En la foto de 1941, Kanji Miyasaka con su esposa, Kesano, y su hijo, Francisco, mientras trabajaba como jardinero en el Central Stewart (ahora Venezuela), en una parte de la provincia de Ciego de Ávila que antes pertenecía a Camagüey. Después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, él se mudó a La Habana, y trabajó en la finca de Pedro Sánchez Abreu, hijo y sobrino, respectivamente, de las reconocidas benefactoras Rosalía y Marta Abreu (el lugar se conoce popularmente como la Finca de los Monos). Sánchez Abreu, siguiendo la tradición familiar, también realizó muchas obras benéficas.

KYUKICHI ISHIKAWA Y FAMILIA

En la foto, Kyukichi Ishikawa con su esposa, Zoila, e hija de igual nombre. Su hija le cuenta a Benita Eiko Iha Sashida en el libro Shamisén que su padre trabajó como jardinero en La Habana, antes de mudarse para Pinar del Río y dedicarse a la agricultura.

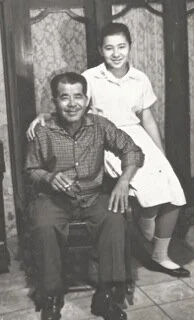

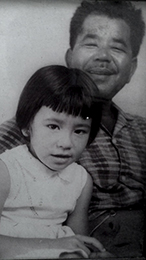

ZENSHUN ISHIKAWA Y SU HIJA

En la foto de 1964, Zenshun “Manolo” Ishikawa (hermano de Kyukichi Ishikawa). Su nieta, Sayuri Martínez Ishikawa, cuenta que él trabajó en el cultivo de flores en Pinar del Río, y que a mediados de la década de 1950 “trabajó durante mucho tiempo como jardinero en la residencia de una doctora, en el barrio de Miramar” en La Habana. Su hija, Isabel Ishikawa, recuerda que “una de las últimas cosas que su padre hizo como jardinero fue trabajar en el injerto de la conocida rosa búlgara”. Después pasó a trabajar en la Flota Cubana de Pesca.

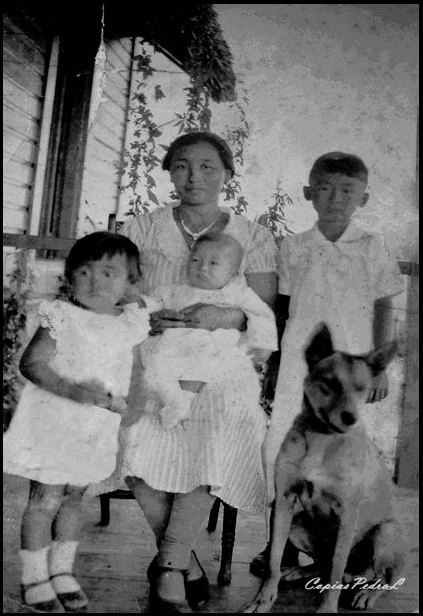

KAMAICHI IHA Y FAMILIA

En la foto de 1953, Kamaichi Iha y su esposa Kame con sus hijos, Manuel Miyuki y Julio Shigeru, y sus hijas, María Mitsuye y Benita Eiko. Benita escribe en el libro Shamisén que después de asentarse en Isla de Pinos en 1930, su padre "comenzó a trabajar como jardinero con un norteamericano en el lugar conocido como Santa Ana". Después se dedicó a la agricultura.

Heikichi Mori Takiguchi

En la foto, Heikichi Mori Takiguchi. Su nieto, Alfredo Mori, cuenta que “cuando mi abuelo llegó a Cuba se asentó en Camagüey, donde había una colonia japonesa. Allí trabajó en el Central Constanza, como jardinero en la residencia de los dueños del central. Años más tarde se mudó a La Habana, y en el terreno frente a su casa en el municipio Cotorro sembraba diferentes flores y al fondo hortalizas. Me cuentan que mi abuelo enseñó a hacer injertos en las plantas, era un especialista en la materia”.

Kamekichi Toyama (Inoue)

En la foto, Kamekichi Toyama (Inoue). Según su nieta, “trabajó como jardinero en un casino privado que se encontraba en las afueras de Bayamo, ciudad en la que vivió el resto de su vida. Más tarde se dedicó a vender parte de lo que sembraba en una hortaliza que tenía en el fondo de su casa, [allí] sembraba lechuga, habichuelas, algo de berro, también tenía guayabas y plátanos”.

En la imagen, la portada del libro Japoneses en Cuba, de Rolando Álvarez y Marta Guzmán, quienes mencionan a Susumu Ito, Heikichi Mori Takiguchi y Kanjiro Matsumoto. Ito "trabajó en el central Tacajó [hoy Fernando de Dios, en la provincia de Holguín] . . . como jardinero del hotel allí existente”, en el caso de Mori, "[s]us largos años en Cuba los dedicó a la jardinería y la horticultura”, y Matsumoto trabajó como jardinero en el Central Preston (hoy Guatemala), también en la provincia de Holguín.

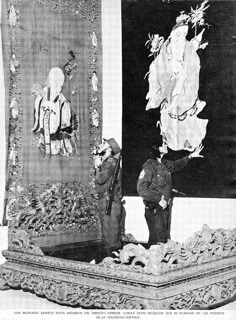

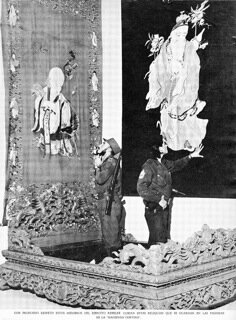

En la foto, un torii que ha resistido el paso del tiempo y que aún puede verse en la Hacienda Cortina. Yuzo Okamoto y Takato Yoshida fueron dos de los inmigrantes japoneses que ayudaron a recrear este “universo oriental” en Pinar del Río.

Como curiosidad: la foto fue tomada en la Hacienda Cortina por el fotógrafo cubano Raúl Corrales, y publicada en la Revista INRA en enero de 1960. El pie de foto explica que las obras estaban en la pagoda de la Hacienda Cortina.

Fotos familiares cortesía de Ana Francisca (Francys) P. Arakawa, Francisco Miyasaka, Isabel Ishikawa, Sayuri Martínez Ishikawa, Julieta Fonte Iha, Narryman Piña Fonte, Alfredo Mori, y Zuleiki Toyama. La imagen y la información sobre la foto y el artículo de 1960 sobre la Hacienda Cortina pertenecen al post "Excursión revolucionaria a la Hacienda Cortina," en el blog Hotel telégrafo. La foto del torii pertenece al artículo "Las bellezas de la Hacienda Cortina," en el periódico Guerrillero. Los testimonios, excepto los de los libros, fueron obtenidos mediante entrevistas en persona o por correo electrónico. La foto del título pertenece a Kennet Schmitz.

© Miharu M. Miyasaka

Cuba's Gardens: Japanese Gardeners

Once in Cuba, the economic aspirations of many Japanese immigrants were channeled through multiple occupational projects. Many kicked off their Cuban journey in the harsh landscape of the sugarcane fields; but for most of them the path of a seasonal sugar-cutter having to work under an inclement and for them unfamiliar tropical weather proved unbearable and soon they left for better jobs in towns and cities.

They followed different professional routes and eventually became gardeners, shopkeepers, barbers, farmers, miners, railway workers, fishermen, and even ice cream makers, among other activities. In general, Japanese immigrants constituted a small and geographically dispersed group that didn’t cause much tension among Cubans; added to this was the fact that none of them ever challenged higher social and professional spaces, and remained in the ranks of the lower working class. Cuban Nisei Benita Eiko Iha Sashida, however, tells a curious story in her book Shamisen about how her mother used to work with her husband (Benita’s father), who was a barber, until she had to stop because it was not well seen by Cubans that a woman had such an occupational role outside her house.

One field in which Japanese were well liked and even sought after was gardening. Due to this Cuban fondness for their sensitivity and skills at cultivating flowers, gardening and/or landscaping, some of them were hired to embellish residences in cities and also in sugar mill estates. In most cases it was a circumstantial occupation, because they weren’t professional gardeners before coming to Cuba.

KANJI AND KESANO MIYASAKA

This was the case of my grandfather, Kanji Miyasaka, who nonetheless became head gardener in the mansion of the administrator of the Stewart Sugar Mill (nowadays Central Venezuela), in Ciego de Ávila province (previously part of Camagüey province). Decades later, from the 1960s onward, he worked as an interpreter for the National Institute of Sports, Physical Education and Recreation (INDER, for its initials in Spanish). Still, I remember how much time and attention he dedicated to the flowers that always filled the terrace and the backyard of his house. His favorite flower was the African violet, and he also had a preference for orchids, hydrangeas and kalanchoes.

Special mention should be given to the Cortina Estate (or Hacienda Cortina, now called La Güira National Park) in Pinar del Río province, with its elaborated garden that included a torii, a pond, lanterns, and a “Japanese House,” among other elements. Rolando González Cabrera explains in the book Japanese Saga in Cuba’s Western Region that Senator José M. Cortina hired Japanese immigrants, among them Yuzo Okamoto and Takato Yoshida, to recreate an “oriental realm” in a section of his remarkably vast estate. And they seemed to have succeeded in the task, grafting a beautiful "oriental" garden into the breathtaking pinareño landscape.

Private gardens, mainly before 1959, became then important sites through which to trace out the presence of Japanese in Cuba.

GOHEI ARAKAWA

In this picture taken between 1948-1952, Gohei Arakawa while working as a gardener in the Baraguá Sugar Mill (nowadays Central Ecuador), in Ciego de Ávila province (previously part of Camagüey province). Arakawa was President of the Japanese Colony in the Baraguá Sugar Mill.

His granddaughter, Francys Arakawa, recalls that her "grand-father was a gardener in the houses of the Americans that worked in the sugar mill." She explains that after WWII Japanese in Cuba were forbidden from working for American citizens; but such policy eventually changed, and he got his gardening job back in 1948.

KENJI TAKEUCHI

In this picture from 1971, Kenji Takeuchi, who became a renowned floriculturist that contributed to the research of flowers, and to the creation of the famous Orchid Garden of Soroa. Francisco Miyasaka remembers that he had previously "worked as a gardener in the estate of Miguel Ángel Quevedo, at the time director of Bohemia magazine, whose property was located in El Chico." Also, that "Takeuchi and a friend had a flower shop near Havana's Christopher Columbus Cemetery, called The Dahlia(or La Dalia). He cultivated the flowers for his shop in a small parcel of land he had purchased in the Wajay."

KANJI MIYASAKA AND FAMILY

In this picture from 1941, Kanji Miyasakawith his wife, Kesano, and son, Francisco, while he worked as a gardener in the Stewart Sugar Mill (nowadays Central Venezuela), in Ciego de Ávila province (previously part of Camagüey province).

After WWII he moved to Havana City, where he attended the gardens of the family estate of Pedro Sánchez Abreu (the place is popularly known as Finca de los Monos). Sánchez Abreu was the son and nephew of renowned benefactors Rosalía and Marta Abreu respectively, and a benefactor himself.

KYUKICHI ISHIKAWA AND FAMILY

In the picture, Kyukichi Ishikawa with his wife, Zoila, and daughter of the same name. The latter told Benita Eiko Iha Sashida in the book Shamisen, that for a brief period of time her father was a gardener in Havana City, before moving permanently to Pinar del Río to work in agriculture.

ZENSHUN ISHIKAWA AND FAMILY

In this picture from 1964, Zenshun “Manolo” Ishikawa (Kyukichi Ishikawa's brother) and his daughter, Isabel. According to his granddaughter, Sayuri Martínez Ishikawa, he worked in the cultivation of flowers in Pinar del Río, and in the mid 1950s he "worked for a long time as a gardener in the residence of a doctor in Havana City's Miramar neighbourhood." His daughter, Isabel Ishikawa, recalls that "working on the grafting of the so-called Bulgarian rose was one of the last things he did as a gardener." He then went to work for the Cuban Fishing Fleet.

KAMAICHI IHA AND FAMILY

In this picture from 1953, Kamaichi Iha and his wife, Kame, with their sons, Manuel Miyuki and Julio Shigeru, and daughters, María Mitsuye and Benita Eiko.

Benita says in her book Shamisen that after settling on Island of Pines in 1930, her father "started to work as a gardener for an American man in a place called Santa Ana." Later on he went to work in agriculture.

Rolando Álvarez and Marta Guzmán mention Susumu Ito, Heikichi Mori Takiguchi and Kanjiro Matsumoto in the book Japanese in Cuba. Ito "worked as a gardener in the hotel that existed in the Tacajó Sugar Mill" (nowadays Fernando de Dios) in Holguín province, Mori "dedicated his life in Cuba to gardening and horticulture," and Matsumoto worked as a gardener in the Preston Sugar Mill (nowadays Guatemala), also in Holguín province.

In the picture, a torii that has stood the test of time and still exists in the Cortina Estate (or Hacienda Cortina). Yuzo Okamoto and Takato Yoshida were two of the Japanese immigrants that helped create this "oriental realm" in Pinar del Río, where they arrived in 1928.

As a curiosity: this picture was taken at the Hacienda Cortina by Cuban photographer Raúl Corrales, and published in Revista INRA in January 1960. According to its caption, the paintings and wood-carved work were found in the pagoda of the Hacienda Cortina.

Family photos courtesy of Ana Francisca (Francys) P. Arakawa, Francisco Miyasaka, Isabel Ishikawa, Sayuri Martínez Ishikawa, Julieta Fonte Iha and Narryman Piña Fonte. The image and information about the 1960's photo and article about the Cortina Estate belong to the post "Excursión revolucionaria a la Hacienda Cortina," in the blog Hotel telégrafo. The photo of the torii belongs to the article "Las bellezas de la Hacienda Cortina," in Guerrillero newspaper. The testimonies, except those from books, were obtained via in-person or email interviews. Title photo by Kennet Schmitz.

© Miharu M. Miyasaka

キューバの庭と、日本人庭師

かつてキューバでたくさんの日本人移民による経済の向上が多種の職業を 通じて、功を奏しました。多くの日本人がキューバの厳しい地形にあるさとうきび農場から去っていきました。それでも多くの人が季節労働者として、熱帯の季節という日本人にとってなじみのない過酷な状況の中で、さとうきびの収穫作業をせざるを得ない人もいましたが、彼らも後に、より良い仕事に就くために、都心へと出ていきました。

彼らは様々な職業の道を選び、結局は庭師、商店の経営、床屋、農家、炭鉱労働者、鉄道員、漁師、そして中には仕事の合間にアイスクリームを作る人もいました。その頃キューバにいる日本人は、地理的にも分散して、小さなグループで成っていたことと、誰一人として、高い地位や職業を得ようとせず、あくまで低い労働者クラスに留まっていたこと事から、キューバからの何かしらの圧力というものはありませんでした。しかし、「しゃみせん」の作者である日系キューバ二世のベニタ E. イシャ・シャシダ は、彼女の本のなかで興味深い事を書いています。彼女の両親は床屋をやっていましたが、お母さんの方が辞めざるを得なくなってしまったというのです。その理由が、キューバでは女性が家の外で仕事をし、さらにその職業が床屋という事が当時では大変イメージの悪い事だったからだそうです。

日本人にとってよく重要のある職業は、庭師でした。日本人の持つ繊細さ、花の栽培、ガーデニングや造園の技術はキューバで高く評価されていました。中には家や、サトウキビ農場の敷地内にお花を装飾するために雇われている人もいました。元はといえば彼らにはキューバにくる前にプロの庭師としての経験はなかったので、庭師という職業は、結果的になったものでした。

私の祖父であるミヤサカ カンジも同じ様な状況でしたが、それにもかかわらず、最終的に彼は今現在シエゴ・デ・アヴィラ州にあるセントラルベネゼエラのスチュアートサトウキビ農場の管理館で庭師長になりました。10年後の1960年台ごろから、祖父は総合スポーツ施設の中にある、国営のINDER (Instituto Nacional de Deporte, Educación Física y Recreación) という、スポーツと、体育とレクリエーションに関する協会のみで働いていました。今だに私は、自分の祖父が自分の家のテラスと庭に、どれだけの時間と努力を花と植物に費やしてきたかを思い出します。

特に忘れずにお伝えしなければいけない場所が、ピナール・デル・リオ州にある、コルティナ地所(またはアシエンダ・コルティナ、現在はラ・グイーラ国立公園)です。この庭園は大変手がこんでいて、鳥居、池、提灯、そして日本家屋が他の日本風の物と一緒におかれていました。ローランド・ゴンザレス・カブレラは彼の著書(“キューバ西部の日本の性″)の中で、上院議員のホセ・コルティナが日本人移民達(オカモト ユウゾウとヨシダ タカコを含む)を彼の珍しい広大な農園の中にある”東洋の園“を改造するために雇ったと記述しています。その日本人移民達は美しい”東洋“の庭園″接ぎ木”をし、息を飲むような“ピナレーニョ”(ピナール州出身の人をこう呼ぶ)の風景を作る仕事に成功したようです。1959年初期に、この私有の庭園はとてもキューバの日本を描く重要な存在になりました。

1930年代の写真では、アラカワ ゴヘイがシエゴ・デ・アビラ州(現在はカマグエイ州に含まれる)にあるバラグア サトウキビ農場で庭師として働いています。アラカワ氏はバラグア サトウキビ農場で働く日本人移民の中での代表者でした。

この写真は1971年からのもので、タケウチ ケンジという、花の研究をし、有名なソロアの蘭園を造る、有名な花づくり師の写真です。フランシスコ・ミヤサカは、エル・チコに位置する、ボヘミアという雑誌の編集長であったミゲル・エンジェル・ケベドの屋敷で過去に庭師として働いていた時を思い出すそうです。そしてタケウチ氏と彼の友達が花屋をダリアと呼ばれるハバナ市のクリストファーコロンブス墓所の近くで経営していたそうです。タケウチ ケンジは自分の花屋で売るための花を、グアハイの中にある、彼が購入した土地の中の小さな一画で栽培していたとの事です。

この写真は1941年からのもので、ミヤザキ カンジが、シエゴ・デ・アビラ州にあるスチュワートサトウキビ農場(今のセントラルベネズエラ)で庭師として働いている時に、彼の妻のケサノ、息子のフランシスコと撮ったものです。第二次世界大戦の後、彼はハバナ市に移ります。ここには、彼が奉仕した有名な恩人であるロザリア・アブレウ家族の大農園の庭園(この場所はフィンカ・デ・ロス・モノスとして有名)がありました。

この写真は、イシカワ キュウキチが、妻のソイラと娘(妻と同じ名前)と写っているものです。後に、ベニタ・エイコ・イハ・サチダが彼女の所著”しゃみせん”のなかで、彼女の父がピナル・デル・リオに農業で仕事を求め移り住む前に、短期間、ハバナ市で庭師をしていたとの記述があります。

この写真は1964年の物で、イシカワ ゼンシュウ(マロノ)というイシカワ キュウキチの兄弟と、彼の娘であるイザベラとの写真です。彼の孫娘のイシカワ サユリ マルティネスによると、彼はピナール・デル・リオにある花造農家で働いていたそうです。そして、1950年半ばには、彼はハバナ市のミラマール近辺あった医者の邸宅で庭師として長い期間働いていたそうです。彼の娘のイシカワ イザベラは、ブルガリアンローズの手入れが、彼の庭師としての最後の仕事だったと、思い出を語ってくれました。その後彼は、キューバの漁の船隊に働きにでたそうです。

この写真は1953年の物で、イハ ケンイチと、その妻のカメ、息子のマニュエル(ミユキ)と、ジュリオ(シゲル)、娘のマリア(ミツエ)とベニタ(エイコ)が写っています。ベニタは彼女の著書の”しゃみせん”の中で、1930年にパイン島に移り住んだ後に彼女の父がサンタ アナというアメリカ人の元で庭師として働き始めたとの記述があります。 その後彼は農業を始めたそうです。

ローランド・アルバレスと、マルタ・グスマンは、彼らの著書″キューバの日本人″の中で、イトウ ススム、モリ ヘイキチ、マツモト カンジロウについて記述しています。 イトウ氏はホルグイン州タカホサトウキビ農場(現在のフェルナンド デ ディオス)にあるホテルで庭師として働いていたそうです。モリ氏は彼の人生を造園と園芸に費やしていたそうです。マツモト氏は、同じくホルグイン州にあるプレストンサトウキビ農場(現在のグアテマラ)で、庭師として働いていたと記述があります。

この写真の中の鳥居は現在もコルティナ邸(ハシエンダ コルティナ)に立っています。日本人移民の、オカモト ユウゾウとヨシダ タカトの2人が、ピナール デル リオに着いた1928年にこの″東洋の国″の制作を手伝いました。

ちなみに、この写真はハシエンダ コルティナにて、キューバの写真家ラウール・コラレスによって撮られたもので、1960年1月にレヴィスタINRAにて掲載されました。その中の見出しには、塗装と木の彫刻が、ハシエンダ コルティナにある東洋の塔で見つかったとありました。

写真への提供への多大なる感謝を、アナ・フランシスカ(フランシス)、P・アラカワ、フランシスコ・ミヤサカ、イシカワ サユリ(マルティネス)、ジュリエッタ・フォンテ・イハ、ナリマン・ピニャ・フォンテに申し上げます。そして、1960年代のコルティナ邸の写真と記事は、ホテル テレグラフォのブログの中の”エクスクルージョン レボリューショナリア ア ラハシエンダ コルティナ”からの引用です。鳥居の写真はグエリレロ新聞の”ラス ベレサス デ ラ ハシエンダ コルティナ”の記事から引用しました。